according to elder holland, what is almost always the metaphor for sexual relationships?

Erotic blooms: The sex appeal of flowers

(Image credit:

Phaidon/Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

)

Robert Mapplethorpe'due south floral photographs have their own sexual practice appeal – and they are function of a long tradition of art that equates flowers with the erotic, writes Jason Farago.

H

He shot jockstraps and bullwhips, sadomasochistic nights out, gents with certain appendages peeking out of their flies. Just Robert Mapplethorpe, one of the preeminent photographers of the U.s. at the terminate of the last century, was no pornographer. Mapplethorpe shot his most explicit images with a cool, detached precision, no more or less lasciviously than he photographed the many other subjects of his gaze.

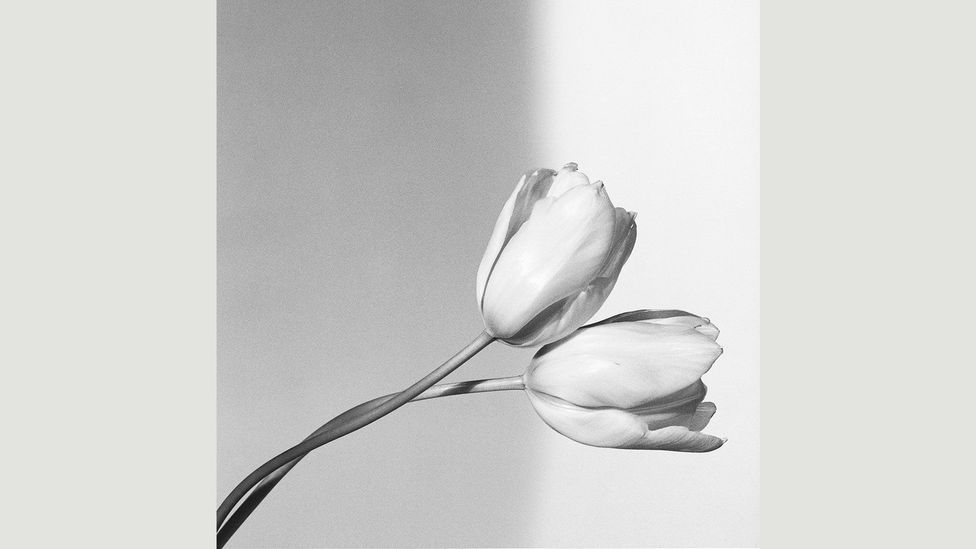

His explicit images, in fact, form merely a modest part of his output, and are outnumbered by studio portraits, studies of the bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, and particularly rigorously composed images of flowers. Calla lilies, tulips, African daisies: these, as much as leather-clad men in flagrante delicto, were the truthful subjects of Mapplethorpe'southward art, the ways through which form became beauty.

Mapplethorpe'due south flower pictures are rigorously equanimous to achieve an aura of absurd detachment (Credit: Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation/Phaidon)

This March is the month of Mapplethorpe, with ii major exhibitions opening in Los Angeles – at the J Paul Getty Center and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art – that draw on the late lensman'south newly acquired archive. (The exhibitions volition travel afterwards to Montreal and Sydney.) The shows coincide with a new publication, Mapplethorpe Flora: The Complete Flowers, which gathers all of his stately, serene floral images into a single book for the first fourth dimension.

Visitors to the LA exhibitions will accept the chance to run across the rough sexual activity of his '10 Portfolio' and the elegant floral images of his 'Y Portfolio' side past side. Only ane of those was greeted with enormous public outcry and, in one case, a criminal trial. Yet the flowers accept their own sex appeal – and are simply one example of a long tradition of eroticised bulbs and blooms.

Early blossom

Between flowers and sexual practice there has long been an enduring link. In the classical age, women (especially virgins) were compared to flowers, whether in Virgil'southward agronomical Georgics or else in Sappho – who, in i fragment, makes an analogy between a woman, perhaps married, and "a hyacinth in the mountains that the shepherds trample with their feet." Shakespeare frequently resorted to botanical metaphors for females, higher up all in Hamlet, in which Ophelia strews flowers all over Elsinore. You need only think of the names Rose, Lily, Daisy, Violet… Women's names, all of them.

Flowers are complex symbols, and they are certainly not always lubricious; the lily, for one, is associated with the Virgin Mary. They are more austere and reserved symbols in East Asian and Islamic decorative arts, or else in the fine art of 17th-Century Holland, where tulips cost more paintings.

When things get-go getting really sexy is the 18th Century, when the botanist Carl Linneaus classified the earth's organisms co-ordinate, in function, to their means of reproduction. Linneaus's Species Plantarum of 1753 did not just pin down all the known globe's vegetation with Latin names. It established that plants reproduced sexually – and offered a scientific, rational footing for the analogy of humans (ordinarily women) to flowers.

The titular prostitute in Manet'south Olympia covers her genitals – simply the blossom in her hair and the bouquet on the left stand in for what she covers (Credit: Édouard Manet)

In the 19th Century, both in England and in France, floral metaphors for women's genitals started to, well, blossom. In Manet's Olympia, i of the signal paintings of the nineteenth century, the titular prostitute covers her genitals with her left manus. Merely she has a pink camellia in her pilus – a stand-in for her covered sex – and indeed her servant comes in from the side of the composition begetting a bouquet of flowers.

The boutonniere is a gift from a customer, in ane sense, but not only that: the flowers bespeak that this woman is on the market. (The illustration is a wide one: in Japan geishas worked in hanamachi, or 'blossom towns', while in China brothels were euphemistically referred to as the 'flower market'.)

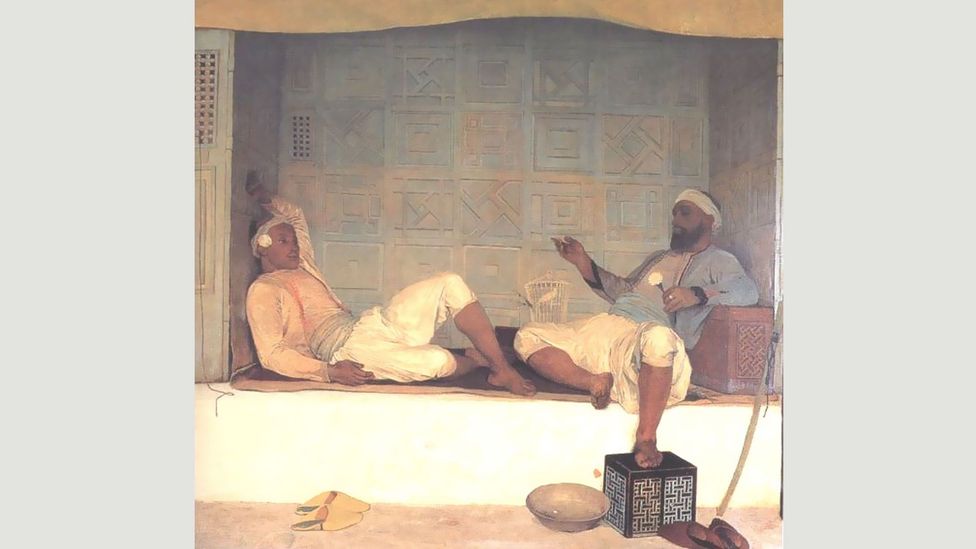

And flowers could bespeak sexual availability not simply for women but for men. The British interwar painter Glyn Philpot, in his Après-midi tunisien, depicts an older, disguised man in the Maghreb, lounging with a boy on a recessed bench. You could about believe the two were equals – until yous come across that the younger gent has got a carnation backside his ear, and the elder is toying with the same flower in his easily.

In the woozy Orientalist fantasy of Guy Philpot'southward Après-midi Tunisien, the flowers signal the sexual availability of the two men to each other (Credit: Glyn Philpot)

Philpot's niggling Orientalist fantasy is no masterpiece, but it points to something important: when it comes to erotics, flowers demand not always be feminine. For gay artists, in fact, the hermaphroditism of flowers – most have both pistils and stamens – had a particular symbolic entreatment. Mapplethorpe'due south stately photographs of calla lilies, with their thick stems and asymmetrical lips, phone call to listen Oscar Wilde's exultation of the same flower, which became a symbol of the Aesthetic movement in Victorian England. Marcel Proust, in Sodom and Gomorrah, makes an analogy betwixt Baron de Charlus'due south sexual encounter with a tailor and the fertilisation of an orchid. And John Singer Sargent – whose sexuality is unattested, simply who remained a available and who painted numerous gay men and lesbians through his career – as well turned often to flowers. His Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, in which two young girls light lanterns among a field of flowers, was described at the time every bit a "self-portrait".

Garden of earthly delights

Past the 20th Century, women artists had begun to draw flowers besides – get-go reservedly, then with abandon. Mayhap no artist has invested flowers with as much eroticism every bit Georgia O'Keeffe, whose big-scale, almost abstract depictions of blossoms and buds transform petals and leaves into flowing, formalist experiments.

O'Keeffe, discipline of a major retrospective this July at Tate Modern in London, resisted the overdetermined reading of her flowers as stand-ins for the female person sex organs, and rightly so; her ambitious paintings extend past mere botanical depictions to a modernist engagement with form and colour. Nonetheless feminist artists of the 1970s noted the undeniable eroticism of her blossom paintings. Judy Chicago, whose installation The Dinner Party (1974–79) is an explicit tribute to O'Keeffe, proffers more than than three dozen place settings for great women in earth history, each of whose plates has the vulvar form of an O'Keeffe flower.

Georgia O'Keeffe's flowers recall female person sex organs just also transform the petals and leaves into abstract, formal experiments (Credit: Alamy/Smithsonian National Gallery of Art)

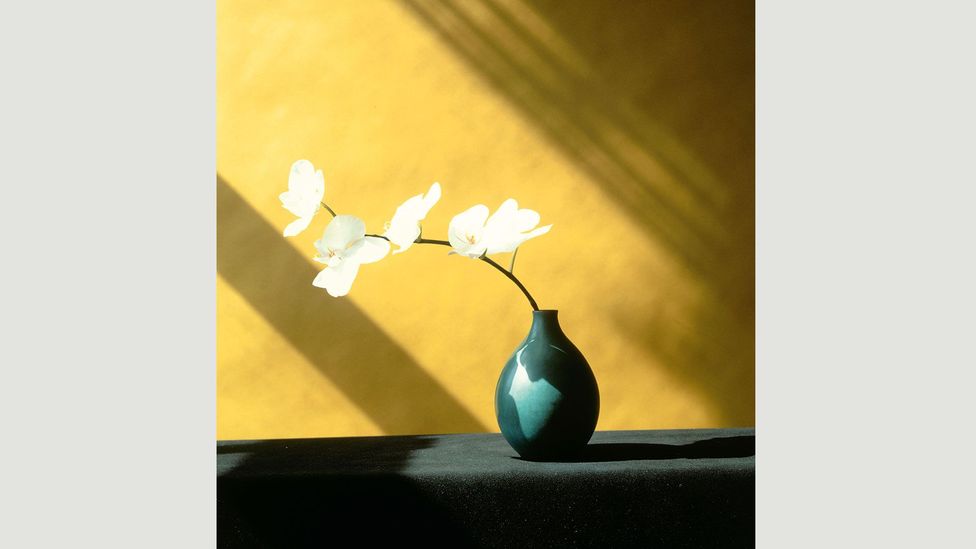

O'Keeffe's flowers were deeply indebted to photography – above all by the images of her friend Paul Strand, whose photographs of plants showroom a similar modernist obsession with getting to the essence of life. And photography, as practiced by artists of both sexes, overtook painting as the principal medium to explore the sex life of flowers. Imogen Cunningham's images of roses and lilies, with their thrusting stigmas and fainting petals, appear as near indecent carnal synecdoches.

Edward Weston, another master of blackness-and-white floral photography, found the erotic side of peppers – shooting their curving surfaces with the same attention others brought to (man) nudes. And even by the belatedly 20th Century, when more explicit sexual imagery had become commonplace in the domain of contemporary art, flowers notwithstanding functioned every bit a vehicle for sexual metaphor. Consider Nobuyoshi Araki, the Japanese photographer who is to heterosexual sadomasochism what Mapplethorpe is to its gay variant. He remains best known for his images of women trussed up in e'er more baroque rope bondage. Nonetheless for more than than three decades Araki has also shot erogenous, up-close colour photographs of lilies, roses, and tulips, his lens thrust betwixt their petals with almost indecent immediacy.

Mapplethorpe hoped his bloom pictures would brand people see his overtly sexual photos in a dissimilar light (Credit: Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation/Phaidon)

Honey is a flower, John Lennon sang; life itself is a bloom, if yous can trust Ace of Base. Nosotros invest them with almost unsupportable symbolism. And even in our contemporary moment, when it seems no representation is too explicit, we still need flowers to represent something across themselves. Besides much so, possibly.

Mapplethorpe, towards the cease of his too brusque life, explained that his early homoerotic and sadomasochistic photography had overwhelmed the interpretation of his flower images – a sentiment that O'Keeffe would have understood, just against which Araki would surely bridle. "I thought that information technology would brand people run across things differently," he said. "But what happened was that they took the cocks and fused them onto all the other [pictures] instead of the other way effectually." Sometimes a flower signifies a more lascivious thing, and sometimes a bloom is just a flower.

If you lot would like to comment on this story or annihilation else you take seen on BBC Civilisation, head over to our Facebook folio or message united states of america on Twitter .

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160303-erotic-blooms-the-sex-appeal-of-flowers

0 Response to "according to elder holland, what is almost always the metaphor for sexual relationships?"

Post a Comment